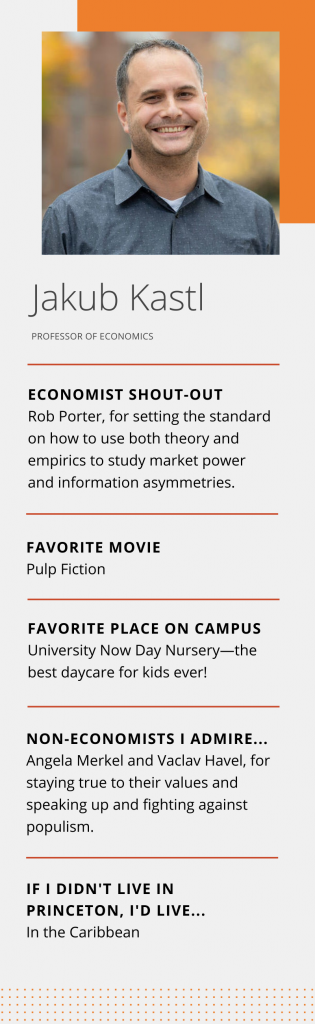

Office Hours with Jakub Kastl

If Jakub Kastl could live anywhere, you’d probably find him beach-side in the Caribbean or on the slopes in the Rockies. But as a professor at Princeton, he has no complaints about life in New Jersey.

If Jakub Kastl could live anywhere, you’d probably find him beach-side in the Caribbean or on the slopes in the Rockies. But as a professor at Princeton, he has no complaints about life in New Jersey.

“I love how much people walk around here,” he says. “It almost has this European, small-town vibe.”

A native of the Czech Republic, Kastl graduated from Charles University in Prague before earning his PhD at Northwestern University in Chicago. After several years at Stanford, Kastl was awarded the prestigious Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Research Fellowship in 2014. The next year, he joined the faculty at Princeton.

For Kastl, it’s the connections and collaborations between various fields that makes the study of economics at Princeton so special.

“At Princeton, we have a really strong finance group that’s part of the economics department, and that’s really unique and valuable,” he says.

Studying big economic questions with rideshare data

Working in the field of industrial organization, Kastl studies market design across a broad range of markets, from demand for government debt to auctions in financial markets and even studies of rideshare apps.

In a study that uses data from a large European rideshare app, Kastl and his co-authors, including Princeton’s Nicholas Buchholz, make an important contribution to a topic of great importance in economics: How people value their time.

Highlighted Research

❱ The Value of Time: Evidence from Auctioned Cab Rides

with Nicholas Buchholz, Laura Doval, Filip Matejka, and Tobias Salz

In the ride app, customers bid on ride requests that involve trade-offs between price and waiting time. Studying auctions for 1.9 million ride requests and 5.2 million bids, the researchers lend empirical evidence to the idea that how people value their time varies by place, person, and time of day, with riders, as a group, being much more willing (16%) to pay a higher price during work hours.

However, they show that the primary factors in determining a person’s willingness-to-pay are individual. Once those differences are accounted for, only a small fraction of the variation in willingness-to-pay is due to location and time of day.

The researchers say their demand model of trade-offs between time and money can be used to improve the design of a range of services and markets.

In future work, Kastl aims to gleam more learnings from the study of rideshare apps. The next question he’s interested in is how changes in the design of a platform could affect the “spatial equilibrium” among drivers and riders, i.e. where drivers locate themselves and how that affects prices, waiting times, and other factors.

“Study what you truly enjoy learning about.”

As his work with rideshare apps demonstrates, Kastl says the key to research is to always be on the lookout for exciting new data sources, and to study what you truly enjoy learning about.

For Kastl, the study of economics at the undergraduate or graduate level “opens up many possibilities and teaches students the important skill of how to think on the margin.”

Kastl says working with his students on their research papers is his favorite thing about teaching, and that his proudest moment as a teacher was when two of his graduate student advisees–Giulia Brancaccio and Molly Schnell–were named among the top candidates, across all universities, on the job market in a single year.

For anyone new to teaching, his advice for success is simple: “Take it easy, and be ready to admit when you don’t know something.”