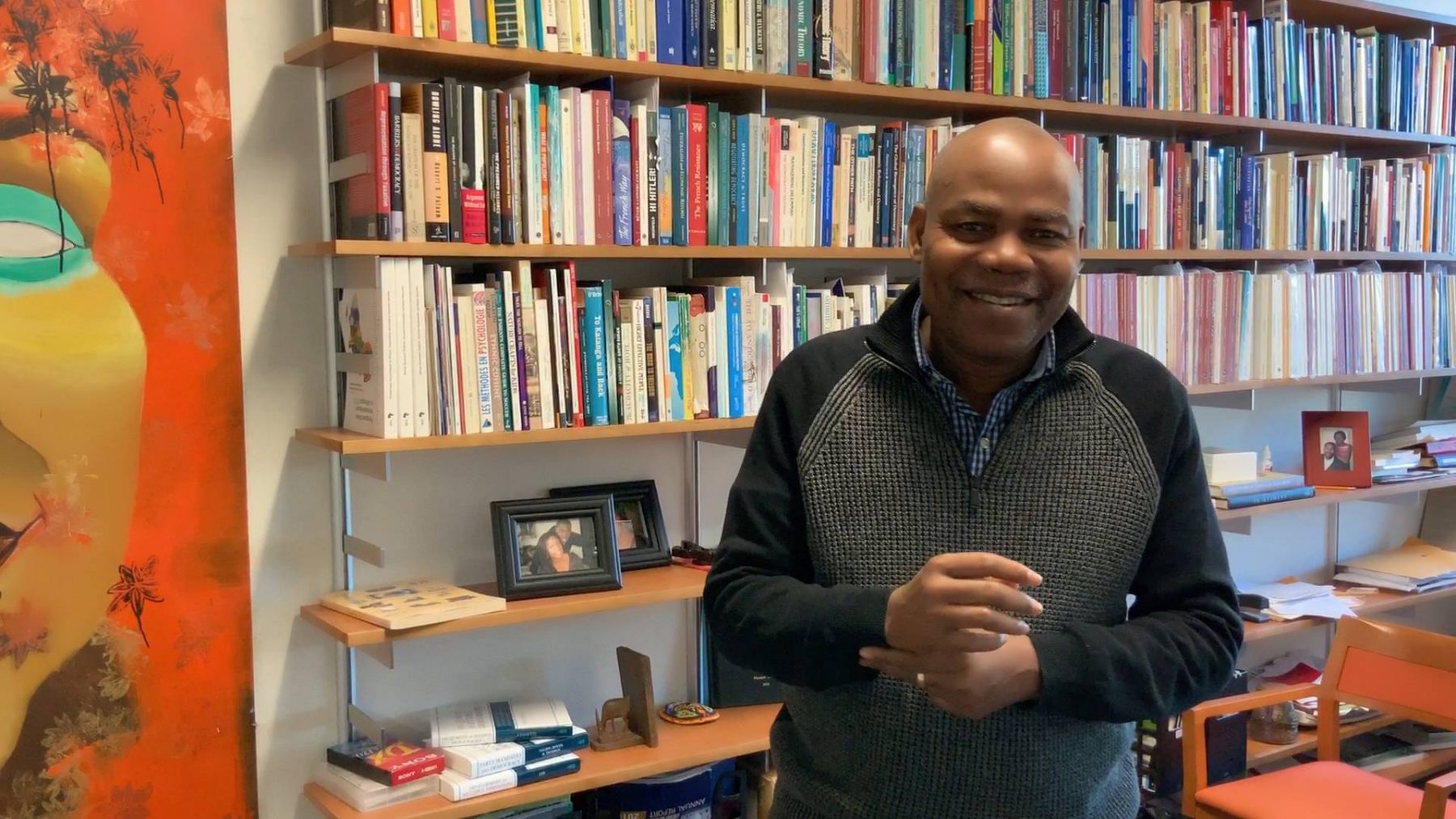

Princeton Professor Leonard Wantchekon leads new effort to propel Black students into top economics Ph.D. programs

In 2014, Princeton professor Leonard Wantchekon opened the doors to what is now one of the top-ranked economics programs in Africa. Today, the African School of Economics (ASE), with campuses in Benin and Côte d’Ivoire, offers several undergraduate degrees, four master’s degrees, a Ph.D. program, and a pre-doctoral program, all aimed at providing “a greater voice to African researchers and entrepreneurs in the debate over the continent’s development.”

Now, Wantchekon is bringing his experience building academic pipelines in Africa to universities in the United States. This month, he announced a new partnership between ASE and Hunter College in New York City that, through a collaboration with Princeton University, will take direct aim at the underrepresentation of Black and minority students in the field of economics. Though African Americans make up 12.6% of the U.S. population, only 3.3% of U.S. citizens and permanent residents that earned a Ph.D. in economics in 2017 were Black or African American. As of May of 2018, Black economists made up only 1.2% of faculty in the top twenty economics departments in the U.S.

Through the new initiative, which focuses on enrollment and programming within Hunter College’s master’s program in economics, Wantchekon and his partners hope to create a deep pool of students prepared to earn admissions at top Ph.D. programs, including at Princeton.

“We complain about lack of diversity [in the field], but it’s not just about demanding it,” Wantchekon said. “We have to be supplying it. We have to say ‘It’s on me, as well.’”

In addition to working with Princeton Economics faculty on the Hunter College campus, students will be given the opportunity to take classes at Princeton, as well.

“We’ve heard a lot of enthusiasm from our faculty about the initiative,” said Princeton Economics Department Chair Wolfgang Pesendorfer. “From the start we’ve been proud to support this effort by Leonard and his partners at Hunter College, and we look forward to contributing as instructors, researchers, mentors, and more.”

Addressing the core pipeline problem

Since its founding only six years ago, ASE has launched twenty of its students into competitive Ph.D. programs in the United States and Europe. Having developed an impressive proof of concept in West Africa, Wantchekon feels confident those learnings can inform the new collaboration in the United States.

One significant part of the pipeline problem in economics, Wantchekon says, is the rigorous quantitative training required to be admitted to top economics Ph.D. programs. While some undergraduate students at leading research universities in the U.S. have access to the type of graduate-level coursework required, many don’t. And even within undergraduate economics programs at these institutions, where many students receive this training or mentorship, enrollment of Black students remains stubbornly low. If we rely on these feeder systems to diversify the field, he says, progress will be slow, if it happens at all.

“We have to create a conduit for these students who didn’t go to top-tier research universities. Top economics Ph.D. programs have one Black student every 4-5 years, but they should have two or three every single year.”

“African American representation in the field is important, and Harlem is the place to make it happen.” – Leonard Wantchekon

When it comes to building a community where underrepresented students can thrive, location matters, according to Wantchekon. In his discussions of the project, Wantchekon stressed the importance of the program’s new campus in Harlem, which he sees as the cultural capital of the African diaspora in the United States.

“The more I thought about it, the more I realized what Harlem means for the African diaspora and the African American community. The political, cultural, and social history of African Americans happens, in large part, in Harlem. African American representation in the field is important, and Harlem is the place to make it happen.” Location, he says, is one part of what made working with Hunter College so attractive.

Wantchekon wants students in the new program to embrace their culture and experiences and use them to strengthen their research and contributions to the field.

“For minority students applying to a Ph.D. program, they need math, econometrics, and theory. But they also bring in-depth knowledge of the African American and African diaspora experience.” This knowledge is important to the field, he says, and should be nurtured.

Wantchekon also hopes the location will help underrepresented students build a community they can rely on for ongoing support throughout their career.

“Not only will students be trained at the very highest level, but there will be a strong cohort effect. Instead of being the only Black student in your program, you’ll be one of 20, 30, or 40. Support will be provided both inside and outside the classroom, academically, but also socially and culturally.”

While recruitment for the new program will aim to admit at least half of its students from schools in the United States, including historically Black colleges and universities, it will also aim to increase diversity among international students in economics by recruiting Black students and other minorities from Latin America, particularly from Brazil and Colombia, and elsewhere around the globe.

Next steps

The new program will be up and running by fall 2021, with the first students admitted next spring and beginning preparatory work in the summer.

But importantly, Wantchekon notes that the new program is just a first step in his broader plan for addressing the pipeline issue. He sees many more possibilities, in the future, to continue strengthening the collaboration between Princeton and the program at Hunter College.

“Maybe in several years, we’ll have sent 40 or 50 underrepresented students to competitive Ph.D. programs. Think what a difference we can make. And if others get inspired and create similar programs around the country, then we can have several Black students in top Ph.D. programs every year.”

Sign up to receive email alerts when we publish a new working paper.