July 2020

While researchers have long documented that a poor distribution of capital drives economic inequality across countries, how foreign capital inflows can improve financial stability in lower-income countries remains an ongoing debate. On the one hand, opening up to foreign capital markets might reduce funding constraints in low-income countries where formal credit markets are limited. On the other hand, it may worsen the allocation of capital if foreign investors prove to be ineffective at processing and monitoring soft information in markets they don’t understand.

In a recent NBER working paper (PDF), Princeton’s Adrien Matray and UCLA’s Natalie Bau study policy changes in India that provide new evidence that countries do, in fact, benefit from better, more liberal access to foreign capital. These positive effects are especially prominent in areas where local banking markets are underdeveloped.

Specifically, better access to foreign investment for firms in India that were previously capital constrained reduced capital misallocation, increased firm revenues by 25%, lowered prices for consumers by 15%, and increased aggregate industry productivity.

Methodology and setting

To perform their analysis, the authors study the staggered introduction across states of policy changes in India that allowed for the automatic approval of foreign direct investment (of up to 51% of a domestic firm’s equity) into industries where such investment was initially restricted.

Given that so much of India’s bank and bankruptcy regulation is decentralized at the state level, the authors were also able to compare the effects of the influx in foreign investment into areas where firms have more or less access to local bank credit.

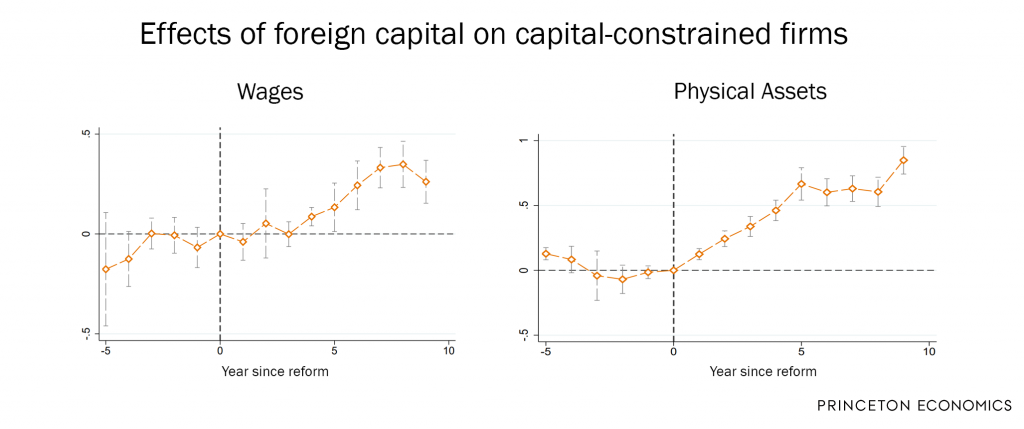

To compare the effects of the influx of capital on firms that were more or less capital constrained prior to the reform, the authors rank firms according to their pre-reform marginal revenue return to capital (MRPK). Firms with high pre-reform MRPK were more capital-constrained.

Benefits for firms, consumers, and the economy

The authors find that the influx in foreign capital benefited not only firms, but also consumers and industries as a whole.

Firms that were previously capital-constrained increased their revenues by 25%, expanded their assets by 57%, and spent about 27% more on labor. Overall, the MRPKs of capital-constrained firms fell by 35%, meaning that the cost of capital for these firms fell, as did capital misallocation. Importantly, the authors found no significant effects on firms that were not previously capital-constrained.

The effects were especially large in parts of India where local banking markets were underdeveloped. These areas (states in the first quartile of the domestic financial development distribution) saw a 50% greater effect than states with more developed local banking markets (states in the top quartile of the domestic financial development distribution).

Firms weren’t the only winners, though. The authors also found numerous benefits for consumers as firms produced more goods and introduced new products—often at lower prices. Firms that were previously capital constrained (again, as defined by having high pre-reform MRPK) reduced prices by about 15%.

Finally, the authors studied whether the increase in foreign direct investment increased aggregate industry productivity by measuring the Solow residual (a common measure of productivity growth) of previously capital-constrained firms. The authors found that the influx of foreign investment increased the Solow residual of different affected industries by between 4% and 17%.