Five Myths about U.S. Immigration and the American Dream

U.S. politicians have always talked a lot about the dangers of immigration. From fears of Southern and Eastern European immigrants in the 1920s to the anti-immigration rhetoric of the Trump administration, claims that certain types of immigrants can never truly join American society have remained a part of our discourse.

After a decade of study of the data on immigration in the past and today, we’ve come to believe that immigration is one of the most misunderstood topics in American public life. Most of the things that voters believe about immigration today–both on the left and on the right–are based largely on myths, not facts.

Armed with 100 years of big data on immigrant families, we can separate fact from fiction. In our new book, Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success, we used frontier methodologies to compile new data on millions of immigrant families from the Ellis Island generation and today. What we find is an uplifting story about the promise of immigration, not only for individuals but for U.S. society as a whole.

By knowing the truth about immigration, we can create policy rooted in data and facts, not fears or misguided opinions. With that goal in mind, here are five immigration myths that are dispelled by the (big) immigration data.

Myth 1: More immigrants than ever are crossing U.S. borders.

Commentators warn of an “immigration crisis,” but the truth is that immigrants today make up the same share of the population as they did 100 years ago.

Today, immigrants make up 14% of the U.S. population. During the Age of Mass Migration from Europe from 1880-1920, the same share of the U.S. population was born abroad (14%).

Myth 2: Immigrants in the past got rich quickly and rapidly became “American,” but immigrants today lag behind.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. Immigrants today move up the economic ladder at the same pace as they did 100 years ago. They also take active steps to adapt to U.S. society–learning English, moving out of immigrant neighborhoods, marrying U.S.-born spouses, and giving their children American-sounding names–at much the same pace as in the past.

Listen: Are Immigrants to the U.S. Assimilating as Fast as They Once Did? (NPR On Point)

For many immigrant families, both today and a century ago, real economic mobility happens in the second generation. Though we often hear that Ellis Island immigrants could go from rags to riches in a single generation, the truth is that most of the time they didn’t. Even back then, immigrants who started out earning less than U.S.-born workers failed to catch up in their lifetime.

Myth 3: Children of immigrants come from poverty and stay poor.

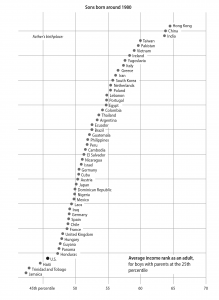

The children of immigrants, both today and in the past, are very economically mobile. In fact, we find that children born to immigrant families are more economically mobile than children with U.S.-born parents who grow up in similar households.

The children of immigrants, both today and in the past, are very economically mobile. In fact, we find that children born to immigrant families are more economically mobile than children with U.S.-born parents who grow up in similar households.

More: Children of Poor Immigrants Rise, Regardless of Where They Came From (NYT)

Despite the fact that children of immigrants are raised in poorer households, they’re able to reach the middle class and beyond. This is true for families today from nearly every sending country, including from poorer countries like El Salvador, Mexico, and Laos.

Myth 4: Immigrants harm those born in the U.S. by taking jobs and committing crimes.

The data tells us the opposite story. Today, immigrants tend to hold jobs that have few available U.S.-born workers, including positions that require advanced education like those in tech and science, and jobs that require very little education like picking crops by hand, washing dishes, or taking care of the elderly.

In studying the effects of past immigration restrictions–such as the major closure of the border in the 1920s–we find that restrictions had unintended consequences. Instead of benefiting the U.S.-born workforce, restrictions pushed many industries toward automation or toward finding other pools of workers (Mexicans and Canadians in the past, perhaps offshoring today).

More: Trump Wants to Limit Immigration to Protect Jobs. Will it Work? (Washington Post)

Finally, despite what we hear on TV, immigrants are less likely than those born in the U.S. to be arrested and incarcerated for all manner of offenses. This was true in the past, and is actually more true today.

Myth 5: The American public doesn’t support immigration.

Despite a vocal anti-immigration minority, a wide range of opinion polling tells us that the American public has never been more supportive of immigration. What’s more, our review of 150 years of Congressional speeches shows that political rhetoric is more favorable toward immigration now than in the past, though noticeably more polarized by party.

If you want to learn more about the past and present of U.S. immigration and the American Dream, Streets of Gold is now available at your favorite bookstore.